All About Aurora Postage Stamp Trains

Servicing Older Locomotives

Introduction

The Trix F-type diesel is a venerable old model that was built to last. Even after a half-century, they can still perform well—but only with proper servicing. While the service manual shows how to dismantle a diesel, it doesn't include proper service procedures you need to perform in order to keep these locos running reliably, which is especially important for older locos that have been sitting idle for a long time. They're not much different than your car.

This bears repeating: There are service procedures you need to perform in order to keep your locomotives running reliably, which is especially important for older locos that have been sitting idle for a long time.

While some locomotives may survive being put into service decades after they were manufactured, others will not, and may wind up being literally tortured to death. It depends on how much they've been run, how much service—if any—they've received, and other variables. I've examined over two hundred used Trix diesels alone, and the vast majority of them show no signs of having been properly maintained (it's a testament to Trix engineers that they continue to run despite frequent neglect or abuse nearly half a century after they were made).

Note that these procedures are applicable to the Donkey Steam Switcher, the 0-6-0 Steam Locomotive, and other model locos from this period as well; some of the specifics will just be a little different.

Maintenance and Restoration

I've found the most effective way restore an old loco that's been in storage a long time is to simply disassemble the entire thing. It's not that hard; the service manual provides an excellent guide. This is better than doing "spot" maintenance because you'll get to see things you may otherwise miss. After dismantling the loco:

- thoroughly clean all mechanical parts with a small, stiff brush and alcohol

- check the condition of the parts by referring to the images shown above

- apply model oil very sparingly to the motor and drive train bearings (lubricating the truck bearings is more easily accomplished before they're reinstalled in the chassis)

- apply a tiny amount of model grease to the worms—it will work its way into the entire gear train when the loco is run

- remove any excess lubricant

- ensure the drive train moves freely by rotating the motor armature with your fingertip; disassemble and reassemble as needed to correct any binding

- test the loco before replacing the shell

The following examples have all been drawn from the stockpile of used locos I've accumulated over the years, so they represent real-world conditions.

|

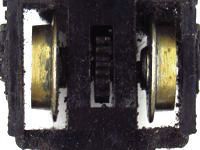

General dirt. Owing to a combination of lubricant and static electric charges, trucks are magnets for lint, dust and dirt, which will accumulate around wheels, wipers and gears. Any dirt should be removed with a tweezers, and the truck should be blown out with compressed ("canned") air. Regularly vacuuming your layout can help prevent this problem. |

|

|

Wheel crud. The most common loco performance problem is wheel crud, which is an accumulation of dust and dirt compacted into a tough film (it's not carbon, as some will claim). A cloth moistened with alcohol will remove it; a fingernail or toothpick will help get at the crud near the flange. This may be tedious work, but the reward is smooth performance. Regular track cleaning (vacuum, then wipe the rails with a cloth moistened with alcohol) can help reduce wheel crud buildup. |

|

|

Dried lubricant. Over time, oil and grease can turn to a yellowish paste or a dry, dark brownish-grey residue. Once this happens, it's useless. Dried lubricants should be removed before applying fresh, because the residue can draw good lubricant away from moving parts. Rinse away dried lubricant with a small, stiff brush wet with alcohol. To clean sintered bronze bearings, leave them soaking in alcohol for a day or two. |

|

|

Oxidized wipers and contacts. Wheel wipers are made from phosphor bronze, which oxidizes if a loco isn't run for a long time. The contact plate under the motor where the wheel wipers touch also oxidizes. They can be cleaned by gently rubbing them with a cotton swab and a very small amount of ordinary metal polish, such as Tarn-X. Rinse everything thoroughly with alcohol afterward. |

|

|

Worn wheels. Wheels are made of brass that's plated with nickel, and the plating on very high mileage locomotives may be worn off the treads. This is a problem because brass quickly oxidizes, and the tarnish inhibits electrical pickup. Worn wheel treads will be dull yellow instead of bright silver, and should be replaced. |

|

|

Loose wheels. The plastic hubs that insulate the wheels from the axles on one side of each wheel set can shrink, causing the wheels to spin freely and lose their gauge. This can be corrected by applying a tiny drop of cyanoacrylate (instant glue) on the hub, and quickly sliding the wheel in place. Be sure to check the gauge. |

|

|

Worn wheel wipers. Extremely high mileage locos may have worn out wheel wipers: the ends will have holes where the contact dimples used to be. These should be replaced. Also check the condition of the plating on the backs of the wheels where the wipers rub, and replace them if they have dull yellow streaks. |

|

|

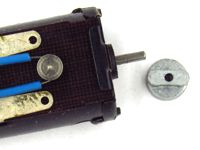

Loose couplings. Soft alloys can become fatigued over time, particularly when press-fittings are involved. For example, the metal couplings attached to the motor shaft may become loose and spin freely. This can be corrected by applying a tiny drop of cyanoacrylate (instant glue) on the very end of the shaft. |

|

|

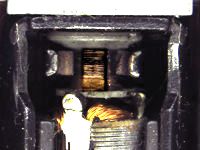

Worn brushes. Motors in very high mileage locos may have worn brushes, which will be smaller and may have worn on an angle. Worn brushes should be replaced. Worn commutator. Although it's quite rare, the motor commutator (dead center in the image) on very high mileage locos may become deeply scored, in which case the motor should be replaced. Note that black streaks on the commutator are normal, and need not be cleaned. |

|

Lubrication

Lubrication is required only once every few years, more or less depending on how much a loco is used. However, be aware of the two most common mistakes modelers make.

Using the wrong lubricants. The rule for lubrication is: grease for gears, oil for bearings. More importantly, you should always use model lubricants. They're not expensive, each bottle will likely last a lifetime (I'm still on my first ones), and they'll add years to the life of your models. Proper model oil is very light, almost like water. Proper model grease is also relatively light, a little thicker than regular motor oil. Model lubricants come in bottles with dispensers made for pinpoint accuracy, which also help prevent the next mistake...

Over-lubrication. Less is more. A little goes a long way. Or, to borrow a brilliant line from the classic railroad film The Train, "A lube job is not a bath!" Excess oil can get into the motor brushes and foul them; it can get on the wheels and cause traction problems; and it can get on your layout and create a mess. Also, most bearings in Trix locomotives are made from sintered bronze, a porous metal that absorbs and retains oil; they do not need to be dripping wet in order to work property. Excess lubricant should be removed before placing a loco back into service.

Spare Parts Stockpile

If you want to keep your Trix locos running well for years to come, it's a good idea to stockpile spare parts, since these locos are long out of production. The most effective strategy is to look for locos with damaged shells or other cosmetic issues; they'll be cheaper, yet provide the parts you'll need, which will mainly be wheels, wheel wipers and motors.