Thinking Outside the Box

6 JULY 2010

It is, undeniably, a painfully over-used phrase. But I cannot conjure one that more aptly describes a means to expand one's modeling options—especially in Z scale, where raw materials are scarcer than they are in larger scales. It's certainly brought success to quite a few of my projects, and since I'm often asked by modelers how I accomplish things, I thought readers might like to have a peek at how I apply out-of-the-box thinking to Z scale modeling.

Tip #1: Ignore the stated purpose. As I'd detailed in my previous post, the easiest and most effective way to break the stock kit stigma and achieve more possibilities is to simply re-purpose a building. Taken to an extreme, one can achieve some fascinating results by looking at kits not as kits but as pools of raw materials. This is often referred to as kitbashing, a time-honored process that can be an extraordinarily powerful technique.

It's a good idea to go so far as to ignore package directions or drawing captions, as this allows one to more easily visualize completely new things. It helps to look only at the parts, or even parts of the parts, and nothing else, and then let your imagination wander. For instance, pulleys for a ship crane can become water main valve handles; portapotty bases can become storm drains; dust collectors can become firehouse sirens... It's startling what you can find when objects are taken out of context.

Tip #2: Disregard the stated scale. Quite a number of items can be effectively modeled in Z by simply making use of related items in N. For instance, the rules that govern plate girder bridge construction in real life is that the bridge components consistently scale up and down, meaning that, as a bridge gets longer, its support members get deeper. Therefore, the proportions of N scale plate girders are correct for Z (or T or HO, etcetera). The detailing—in particular, the rivets—will be slightly oversize, but when painted a dark color and heavily weathered, as many such bridges are, the slightly-too-large rivets and such are barely noticeable.

Another example of N scale items that work in Z is windows. With such an enormous range of possibilities for window sizes and proportions in the real world, many N scale windows are perfectly suited for Z scale structures—especially if they're fine etched brass, where they may actually be superior to the original stock Z scale windows.

Tip #3: Include other hobbies in your search. You'd be surprised by how many useful items can be found outside of model railroading. Supplies for modeling ships, airplanes, even dollhouses can be sources of raw materials that can aid in model railroading. Most useful are etched metal detail parts: ship railings and ladders, airplane vents and grilles, and so on. When combined with Tips #1 and #2, the possibilities expand even more.

Here are some examples of how I've applied these techniques to achieve new results.

One of my favorite examples of "extreme kitbashing" is my movie theater. The building itself was originally a firehouse, while the marquee was made mostly from a car wash! I might not have arrived at this look had I not simply purchased one of almost every Z scale kit made, even the ones that weren't of interest; I had no need for a car wash, for instance, but the parts perfectly simulated the architectural style I sought for the theater.

In another example of unusual kitbashing, the doors on this firehouse (which, by the way, was originally a movie theater) came from an N scale gas station kit.

A pair of dust collector caps from an N scale industrial accessories kit, when perched atop a segment of an N scale etched brass windmill tower, became a Z scale firehouse siren.

All of the windows in this bank came from a British N scale detailing set. They just happened to exactly fit the window openings in the Z scale bank kit.

Meanwhile, the windows on this Z scale farmhouse began life as N scale etched brass transoms that were clipped off of a set of doors.

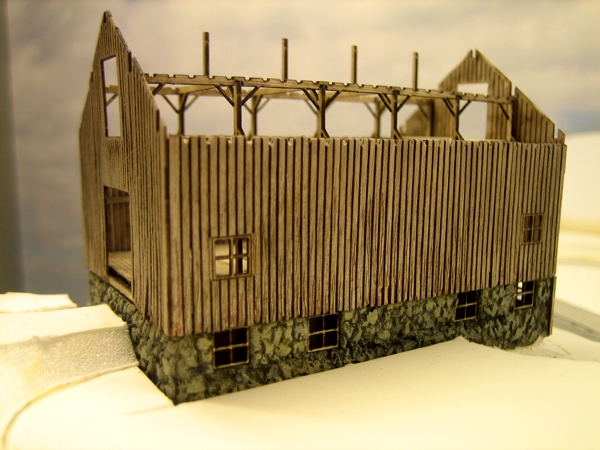

The foundation of this barn was made from pieces of stone wall fence, which I stacked two layers high, then notched for the windows.

In order to make this storm drain, I most definitely disregarded the stated purpose—it was originally part of a portapotty kit.

Pulleys from an old kit for a ship's freight hoist were used to improve the appearance of this water main valve.

The wheel stops on this old coal trestle were spare brace parts left over from a crossing shanty kit.

This old cable-type highway guardrail makes use of railing stanchions from a model ship detailing set (which I'd purchased so long ago that I don't recall the maker or the scale).

These are just a few examples that will hopefully stimulate some outside-the-box thinking—regardless of your modeling scale.